Imagine life before the clock. The Medieval farmer got up with the sun and slept at dusk. The length of their day varied with the seasons. The rhythm of life emerged from the tasks themselves rather than run by an abstract timeline. In this timelessness, how much more vivid and fluid would things feel? Before we invented the concept of ‘time ticking away?’ “Living in deep time,” as Richard Rohr called it.

“The clock does not stop of course, but we do not hear it ticking.” – Gary Eberle

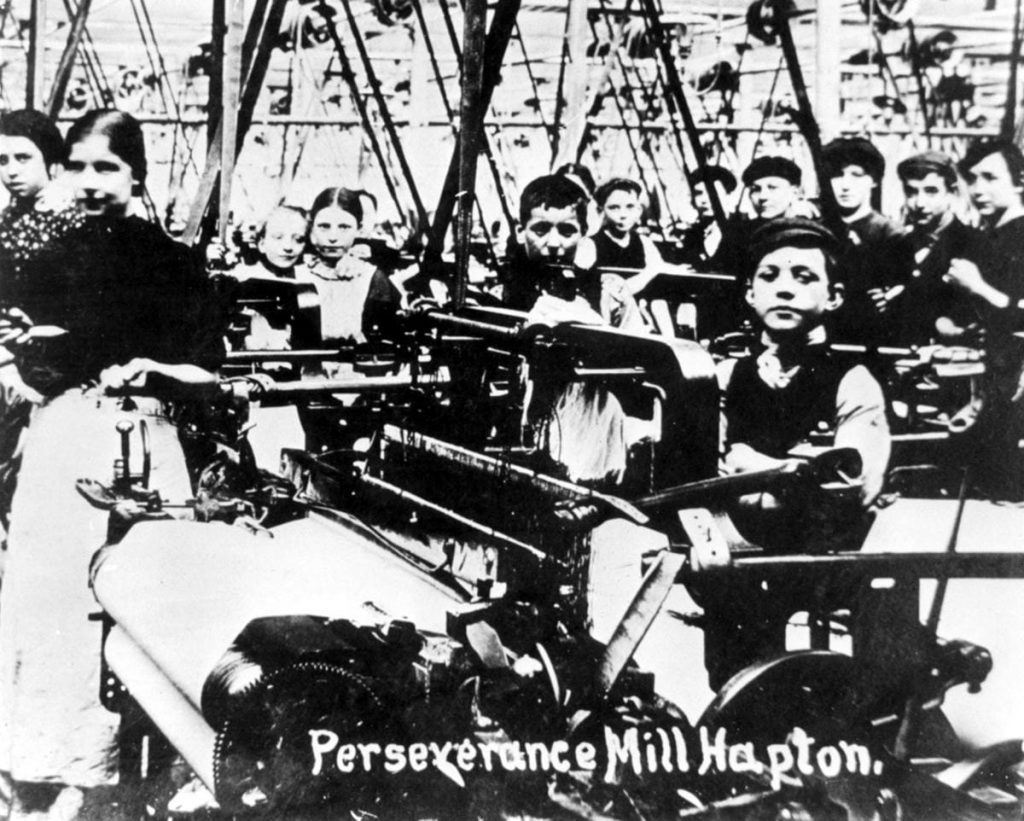

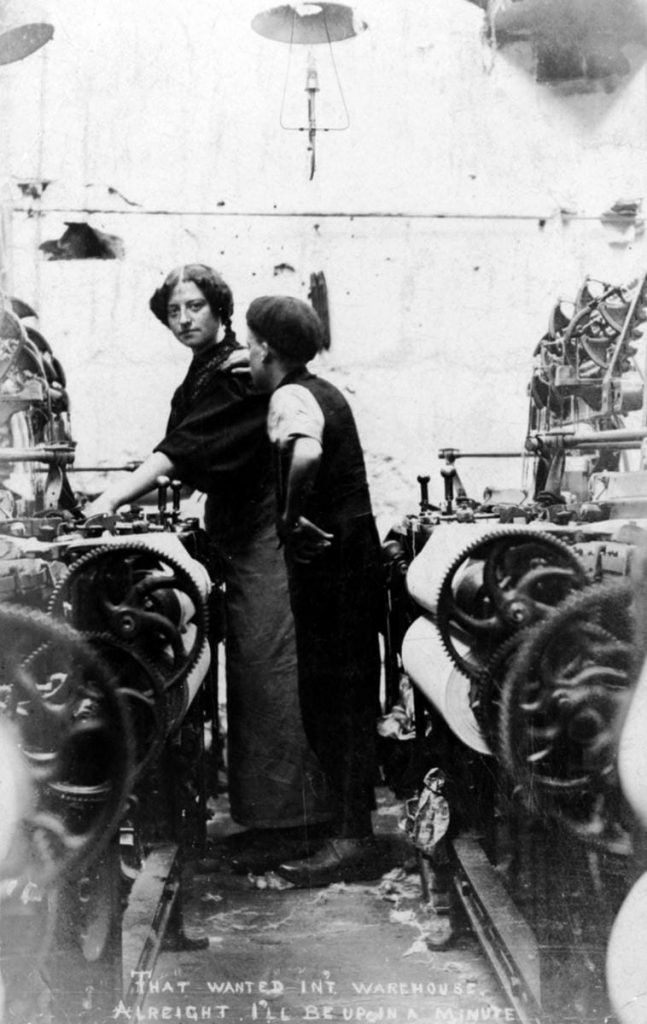

In the mills, time was a resource: something to be bought, sold and used as efficiently as possible. Time became a conveyor belt – workers were paid by the hour and as much work as possible squeezed in to that hour. Time was no longer just the medium into which life unfolded; ‘time’ and ‘life’ became separated – a thing you used. The dictatorship of the clock had begun.

“One thinks with a watch in one’s hand, even as one eats one’s midday meal while reading the news” – Nietzsche, 1887

Read more: ‘Four Thousand Weeks: Time and How to Use it’ by Oliver Burkeman (2021)